Hospitality to Strangers with M. Daniel Carroll Rodas

June 23, 2023

Overview

Speakers

-

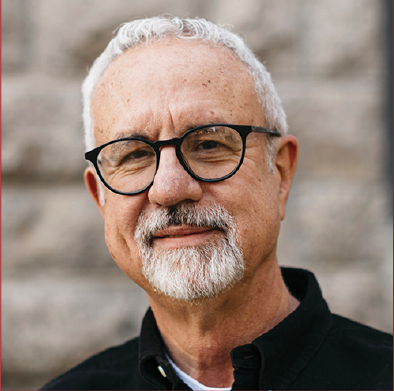

DANIEL CARROLL RODAS

DANIEL CARROLL RODAS -

CHERIE HARDER

CHERIE HARDER

SHARE