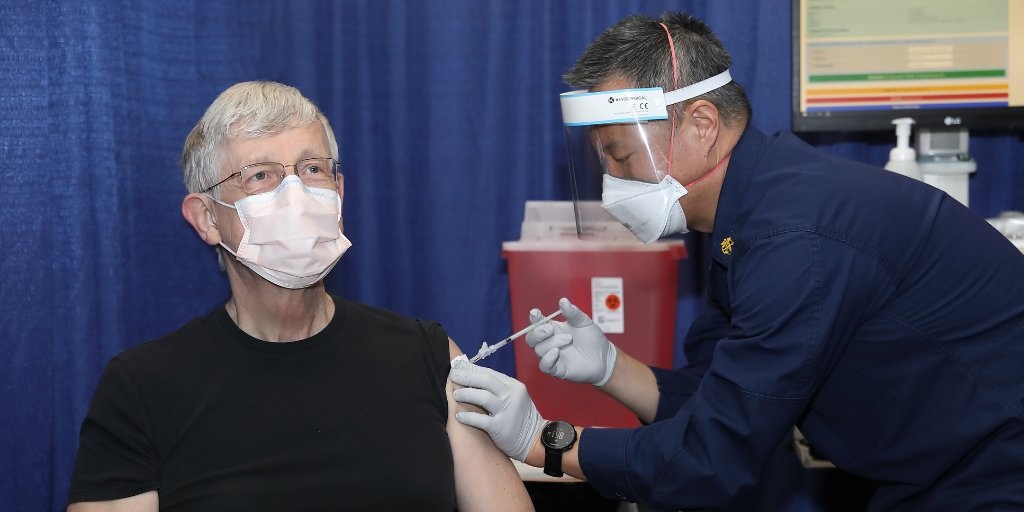

As Francis Collins, the director of the National Institutes of Health, recounted the moment, his eyes welled with tears.

A few months before, he and his colleague Anthony Fauci had confided in each other their hopes for a COVID-19 vaccine. The FDA had set the threshold for approval at 50 percent efficacy, roughly what the flu vaccine achieves each year. They would have been quite happy to hit 70 percent.

Then, on December 9, 2020, Collins received a phone call reporting the first results of the Pfizer vaccine trials. “It was breathtaking,” he told me in a recent interview. “It was just so far beyond what Tony and I had dreamed the answer might be.” The efficacy for the Pfizer vaccine was 95 percent.

“I will admit, I cried,” he said. “A lot of prayer had gone into that.” A week later, Collins received the early results from Moderna, whose vaccine roughly matched the efficacy rate of Pfizer’s. It was a medical miracle.

Collins called the development of the vaccines “one of the most dramatic examples of scientific advancement, especially in the face of a worldwide crisis, that we have had the chance to witness.”

“I’ve been part of other scientific advances that were highly significant, like the Human Genome Project,” he added, “but nobody was going to live or die if we ended up being a couple years late. We weren’t, happily—we were a couple years early. But this one was so different.”

I last interviewed Collins, a longtime friend, in March 2020 for The Atlantic. At the time, he was focused on delivering a warning, which proved remarkably prescient, about the need to control the coronavirus. This time, though, I wanted to ask him about the origins of SARS-CoV-2, in light of speculation that it emerged from a laboratory in Wuhan, China.

“Far and away, the most likely origin is a natural zoonotic pathway from bats to some unidentified intermediate host to humans,” he told me. “But the possibility that such a naturally evolved virus might have also been under study at the Wuhan Institute of Virology and reached residents of Wuhan—and ultimately the rest of the world—as the result of a lab accident has never been adequately excluded.”

That possibility, Collins believes, calls for a closer look. “A thorough, expert-driven, and objective investigation, with full access to all information about events in Wuhan in the fall of 2019, is needed,” he said. “That should have happened right away, but did not.”

Collins was careful to qualify that the coronavirus is “absolutely not” man-made. “The genome sequence of SARS-CoV-2 has a number of unanticipated features that are not consistent with what international experts would have expected from an emerging and dangerous coronavirus,” he told me. “Thus, the hypothesis that this was a human-engineered bioweapon is hard to support. It’s unfortunate that the lab-leak hypothesis has been muddled up with the intentional-bioweapon hypothesis in 16 months of tortured and politically driven rhetoric. That has given way too much credibility to the latter and not enough to the former.”

Senator Rand Paul has accused the NIH and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of funding “gain of function” research into bat coronaviruses at the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV). (Gain-of-function research is intended to make pathogens more deadly or more transmissible for the purpose of producing knowledge that would benefit humans.) But Collins finds such claims misleading. “There’s a terminology problem here that is causing a lot of confusion,” Collins said. “Lots of scientists study harmless organisms like plants and bacteria to try to identify how life works, or how genetic changes might be useful for tackling a medical or societal problem. For example, if you want a harmless bacterium to acquire the ability to clean up an oil spill, you might use a bioengineering approach to provide those bacteria with gain of function to metabolize hydrocarbons into less harmful substances.”

Such research, he explained, is different from enhancing viruses that affect people. “The gain of function that is of much greater concern, and for which the United States has in place stringent oversight guidelines, relates to experiments that might make a human pathogen more transmissible or more virulent,” Collins said. “NIH has never supported such experiments on human coronaviruses. The now-terminated subcontract to the WIV was to support the isolation and characterization of viruses from bats living in caves in China. Since we knew those were the original source of SARS and MERS, it would have been irresponsible not to try to learn more about them. But the terms of the grant were limited to bat viruses, and absolutely did not allow gain-of-function research in the sense of studying human pathogens.”

However the coronavirus first emerged, by the early months of 2020, it clearly posed an enormous challenge. “As soon as you could see this pathogen beginning to spread across the world, we knew that the only way we were really going to have a chance ultimately to vanquish it was going to be with a vaccine,” Collins said. “But the historical record would say that if you worked flat out, you might have something in five years. That’s the best we’d ever done. And yet looking at the rapidity with which this virus was spreading and taking lives, that was simply not going to be acceptable.”

The solution was mRNA: messenger ribonucleic acid. In essence, mRNA can be chemically engineered to instruct cells in your body to produce proteins that mimic some essential feature of a particular virus. The immune system, in turn, builds a response tailored to that virus, so that if the body then confronts the real thing, it’s well prepared.

“Messenger RNA was unprecedented at this scale—there had never been a vaccine approved with messenger RNA—but it was also elegant and very quickly responsive to the need to get started,” Collins said, “because all you needed was to know the sequence of the letters of the viral genome to start making that vaccine.”

The idea of using mRNA to develop vaccines has been around for decades, but it was considered on the fringes of the possible. The concern was that if you injected RNA into a cell, it would set off a wildly rapid and severe cellular inflammatory response, uncontained and uncontrollable. But the Hungarian American scientist Katalin Kariko, now a senior vice president at BioNTech, and her collaborator Drew Weissman, at the University of Pennsylvania, figured out how to chemically modify RNA so that it would no longer set off cellular alarm bells but could still code for a virus’s spike protein. Such an mRNA vaccine could inspire the production of antibodies that could attack a virus with “the precision of a well-trained military,” in the words of The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson.

Animal experiments with an mRNA vaccine began almost immediately after the basic genetics of the coronavirus became known. And just over 60 days after the original sequence of the virus was published—on March 16, 2020, five days after the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic—Jennifer Haller became the first human injected with an mRNA vaccine. “Then I really began to watch closely,” Collins said. “Okay, are the humans making antibodies against the spike protein? That would be a really good sign that this is working. And within a month or so, it became pretty clear they were.”

That was encouraging. “But anybody who’s done a lot of vaccine development will tell you, ‘Well, yeah, but there’re all these other things that are going to go wrong.’ Because they usually do.”

From there, scientists needed to administer the vaccines in a large-scale trial of volunteers, diverse in background, medical status, race, and age.

“We all held our breath,” Collins recalled, “first of all wondering, Will there be some mysterious, unexpected, dangerous side effects now with more than 30,000 people? Will you start to see that? And we did not with the mRNA vaccines. Neither the Pfizer nor the Moderna has had that issue.”

“And then you hold your breath until the day that you know there’s a sufficient safety record, which means half of the people in the trial have to have been followed for at least two months.”

In December 2020 came the phone call with the good news.

Despite this unprecedented breakthrough, the work was hardly done. Collins credits President Donald Trump’s secretary of health and human services, Alex Azar, with moving forward in the spring of 2020 with “at-risk manufacturing,” beginning mass production of the vaccines while clinical trials were still under way. If the vaccines had failed, they would have had to have been thrown out; the money would have been wasted. But instead, the moment the trials were completed, millions of doses were ready to be administered. The Department of Defense was pulled in to assist with distribution. Collins also co-chaired a public-private partnership called ACTIV, or Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines, which developed a coordinated research strategy for prioritizing and speeding up development of the most promising treatments and vaccines.

Today, Collins told me, the challenges are different. “We are no longer limited by supply,” he said. “And it’s time to really try to figure out how, for the folks who are still movable on this, how do we move them into the yes category.” The pace of vaccinations is slowing in the United States; providers are administering about 1.7 million doses a day on average, roughly half as many as the peak of 3.38 million a day reported in mid-April.

“We need to get to 70 to 85 percent, which is the rough guess about when the virus starts to lose,” Collins said. “We still have to work really hard on people who haven’t signed up yet.” As of today, 62 percent of people 18 or older have received at least one dose of a vaccine; 51 percent are fully vaccinated. A few weeks ago, President Joe Biden declared that his administration’s goal is to at least partly vaccinate 70 percent of adults by July 4. Achieving that objective will require making vaccines more convenient for people to obtain, especially those living in rural or hard-to-reach locations, and having trusted authority figures appeal to vaccine-hesitant populations.

Collins acknowledged that he worries about what comes next. Is a variant out there that’s so different from the original strain that the vaccines fall below the threshold of efficacy? India and South America are experiencing a terrible surge of cases; every one of those newly infected people presents an opportunity for the virus to make itself even more dangerous.

“So far, the vaccines that are currently approved in the U.S. do work against the most worrisome emerging variants,” Collins told me. “That includes the B.1.1.7, which was the one that spread rapidly through the U.K. and is now 74 percent of the isolates in the U.S.” He also said that the mRNA vaccines work against the South Africa variant, although the response they generate is not quite as strong, which is why the NIH is already working with Moderna to design and test a follow-up vaccine in case we need it.

I asked Collins whether a booster vaccine for a COVID-19 variant would require a relatively simple recalibration or restarting the entire vaccine process from scratch.

“The FDA fortunately has already thought this through, and with the mRNA approach, all you’re doing is changing some letters in that mRNA code,” he said. “Otherwise, it’s exactly the same vaccine—the packaging and the lipid envelope and all that are all the same—so the FDA would be inclined in that situation to let you do a very rapid trial. You don’t have to do another 30,000 trials and take six months to get the answer.”

The past year has brought many unexpected twists, even for experienced researchers. I asked Collins what had most surprised him about the virus since we spoke last March.

“That it is so readily transmitted by people who have no symptoms,” he told me, pointing to the role that presymptomatic individuals have played in spreading the virus. “That’s unprecedented. That made our public-health measures infinitely more difficult.” With SARS and MERS, which are also coronaviruses, people who were infectious were generally quite sick, and so they were in bed or in a hospital. “With SARS-CoV-2, they were walking around feeling fine until maybe three days later. And the actual peak of infectivity is about two days before symptoms come on. The peak. I mean, it’s diabolical.”

When we first spoke, Collins expressed his hope that we would discover a highly effective therapeutic agent that could be given to people right after they got infected and that would “basically knock the thing out before you ever really got very sick.” But that hasn’t happened.

The big push right now, Collins told me, is “to pull out all the stops like we did for HIV 25 years ago, and come up with really effective, highly targeted antiviral drugs”—for example, a safe, cheap pill that could be given at urgent-care facilities to people who have been exposed to or tested positive for COVID-19—“that will knock this virus out and others like it that may be emerging in the future.”

I asked Collins whether any collateral good might come from this horrible pandemic. “We certainly have learned that this mRNA-vaccine strategy is a winner, and that will be applicable now to virtually any pathogen that we need to make a vaccine against,” he said. “Our vaccines for tuberculosis are going to be revamped as a result of this.” He added that vaccine strategies for cancer are “going to get a big push because mRNA is a much more efficient way to produce what you might be looking for there.” He also mentioned a borderline obsession of his: diagnostic testing.

“By basically turning NIH into a venture-capital organization, we have brought forward no less than 34 really dramatic new technologies for doing testing at the point of care to discover who’s got the virus and who doesn’t. That includes home tests that are now out there that would not have been out there without our having invested all of this in the technology development. So that’s pretty much a game changer. That’s going to change the way we think about doing testing for lots of things.” We will, he said, “move away from the big-box laboratory, where you have to go to deliver a blood sample, to basically doing testing at home.”

For all the progress America has made in vaccine development and distribution—several states in the Midwest and Northeast have reported seeing new cases decline by more than 50 percent over the past two weeks—I wanted to hear Collins’s perspective on what has most unsettled him about America’s response to the pandemic. After all, well over half a million of our fellow citizens died in less than a year because of COVID-19. What is it about our country and our politics that explains the epic mishandling of the COVID-19 crisis?

“You can certainly look at other countries across the world as models of various types of behavior, and ours doesn’t come across as looking admirable for most of the first year of this pandemic,” he told me. “Look at the way in which Taiwan or New Zealand or Australia or South Korea addressed this.” In America, he said, we value our individual liberties and our unwillingness to submit readily to authority. The nature of our society and our individualist, atomized culture meant that the pandemic was going to be less than optimally managed.

“But oh my goodness, it could have been managed better than it was!” Collins said. “The mixing of messages about exactly how serious this was, and about exactly what measures individuals could and should take to try to limit the harms, left many people with a sense of confusion. People were given the chance to pick the option that they liked best and go with that. And oftentimes that was an option that led to more disease. The consequences of that are just absolutely devastating for our country. So, as a national effort to adopt reasonable public-health measures, we failed.”

There are all kinds of reasons for that. We don’t have a national message generator that can always be consistent. We place a lot of the decision making in the hands of local and state leaders; they have not been equally competent during the pandemic. Even as the data began to be more accurately collected, we failed to react to them appropriately. It certainly didn’t help that the most important voice in American life, the president’s, was dismissive of masks one week, promoting hydroxychloroquine as a cure for COVID-19 the next. Trump even suggested using a disinfectant like bleach as a potential treatment, as Deborah Birx, his coronavirus-task-force coordinator, looked on in horror.

Collins described his frustrations this way:

It all got so tangled up in politics, where your political party was the strongest predictor of whether you were going to wear a mask or not, which scientifically makes absolutely zero sense. If you were an alien and you landed on the planet in the midst of a pandemic and you looked around and you saw some people wearing masks and some not wearing masks and you said, “I wonder what that’s about?” and it turned out it was their political party, you would just shake your head and get back on your spaceship and say this planet doesn’t have a future and head off somewhere else, because it’s just bizarre.

“It is both the wonderful way in which our nation has been so creative and so successful by not submitting to authority, but in this instance, when it’s a pandemic, it hurt us a lot. People died,” Collins said. “Surely hundreds of thousands of people lost their lives that didn’t need to.”

As I talked to Collins, I found it difficult to simultaneously hold the conflicting emotions—great sorrow and great gratitude—evoked by two realizations: A single disease has caused carnage and grief unmatched in any of our lifetimes, but because of the work of countless heroes in the world of medicine, many millions survived. Collins and his colleagues have been givers of life in a year of death.

Peter Wehner is a contributing writer at The Atlantic and a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. He writes widely on political, cultural, religious, and national-security issues, and he is the author of The Death of Politics: How to Heal Our Frayed Republic After Trump.