Lincoln’s Sermon on the Mount: The Second Inaugural Address, with Ron White

Speakers

-

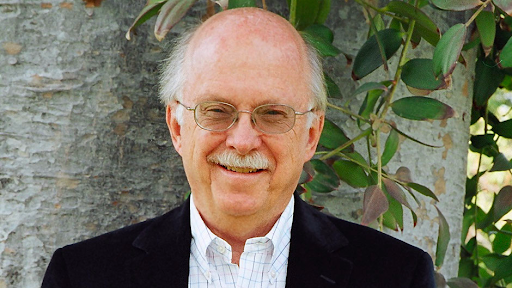

RON WHITE

RON WHITE

Because of the acoustical wood paneling in here. It’s all about spoken word, this room. And it is in conjunction with our debate program, which is on this floor. We’re very proud to host this evening’s event, which is an event that came together because of the cooperation and collaboration with Saint Paul’s School and NDA, thinking that great ideas and Trinity Forum would be an appropriate evening of celebration here in Nashville. And we’re especially proud to have you on here, who’s been a friend of ours now for several years. This is his third visit to NDA, and we’ve enjoyed hearing about Abraham Lincoln and having great conversations together. So I hope you have a wonderful hour of Discussion and thought about Lincoln. This is a great year to do this with the new Spielberg film, which you’ll see a piece of in conjunction with Ron’s talks. I’m also honored to make a brief introduction for our government, and we’re very pleased to have you here. A few years ago, Bill did a great favor for me. I was hosting a debate for high school students in Nashville for the presidential election, and I was having a hard time finding someone to represent John McCain and I all around the state. And I called the mayor’s office in Knoxville, and he picked up the phone and I said, would you come down here to represent John McCain for a number of high school students? He said, absolutely, yes. And I’ve been indebted. It was a great evening, and it was a really good program to do for the high school students in Nashville, and it is an honor to have you on campus, and an honor to have you join me in welcoming him.

I’ll tell you if I project as well as Brad. Does it work? Okay. Well, actually, Brad owes me. Somebody even said, I show up, and at the time, I’m the mayor of Knoxville, so I’m worried about filling potholes and making certain that people’s, uh, you know, basic service delivery happens. And the person who’s, uh, representing, uh, then Senator Obama is Jim Cooper. Yeah. He’s, uh, he’s up in the middle of arguing all these issues that are national issues because he’s in Congress. He also happens to be a Rhodes Scholar. Was a wee bit smaller, smarter than I am, anyway. And so I knew it was bad when in the middle of we’re doing these things where we’re trying to answer the Answered the question as if that candidate was answering them. And one question I asked, and I literally said, I have no idea what Senator McCain said at this point. Congressman Cooper said, well, actually he would say blah, blah, blah. I said, you know, it’s bad when your opponent gives your best answer. Hey, I am thrilled to have you all here. And really, to have the Trinity Forum in Nashville is a bit of full disclosure. My wife, Chrissy, and I have been, uh, participants in Trinity forums. Uh, I can’t remember for how long, but more than ten years ago and have stayed involved, uh, actually stayed involved as donors as well. Uh, because we believe so much in what they’re trying to do. Uh, and I might say the the reason for that is this Senator Frist could could elaborate on this better than I can, but a lot of people talk about, um, the polarity of the different political Parties and how split we are. Bill Haslam: And it feels like that nothing is happening. And people, there’s all sorts of different reasons for that. Well, it’s because the the way they’ve driven, they’ve drawn the congressional lines and people only worry about getting beat in a primary now. So everybody’s going further and further to the to the sides. I actually think it’s driven by something that is a desire for far too many people to seek the simplicity before you get to the complexity of a problem. Uh, somebody here probably knows this quote exactly right. I’ve been quoting it for years, and I probably have butchered it over the years. But Oliver Wendell Holmes said something to the effect of I wouldn’t give a penny for the simplicity this side of complexity, but I would give the whole world for the simplicity on the other side of complexity. In other words, having thought through what the real fundamentally believed to be true and what are the basics of that argument, then you can make a simple argument on the other side. And in my mind, Trinity Forum is dedicated to the proposition that having thought through the big ideas and understand where you are on the big questions of life, the things that are most important to us. That then we can have a whole different discussion on issues which feel really complex. So like I said, as the as the governor of Tennessee, I’m thrilled to have the Trinity Forum here and welcome you. And it’s a personal note. It’s fun for me to see so many friends in the audience as well. So thank you. And we’re honored to have you here.

Good evening to all of you. And welcome to Trinity Forum evening conversation with Ron White on Abraham Lincoln’s Sermon on the Mount, the second inaugural address. I’m Cherie Harder, I’m the president of the Trinity Forum, and someone had to use this big old podium, so I figure I’m the person to do it. We’re really delighted to partner tonight with Brad Gioia and the Montgomery Bell Academy, and Ken Cheeseman and Saint Paul’s Academy in presenting what promises to be a fascinating discussion of the extraordinary leadership and spiritual wisdom of Abraham Lincoln during some of the darkest hours of our country. We’re also deeply thankful, and I just want to recognize our hosts and co-sponsors, governor Bill Haslam and his wife, Senator Bill Frist, my old boss. It’s great to have you back here. Um, Mr. and Mrs. Joe Cook, Mr. John Rochford and Byron and Beth Smith and I should acknowledge from the outset that Byron has really been the visionary catalyst behind tonight’s gathering. He stays in the background, but has been just really incredible in bringing all this together. For those of you who aren’t familiar with the Trinity Forum, we exist to provide a space and resources for leaders to engage life’s biggest questions in the context of faith. And we do this by trying to provide readings and publications which draw upon classic works of literature and the timeless wisdom of the humanities, and connects it with timely issues, and also by sponsoring programs such as this one tonight, to connect leading thinkers with thinking leaders and engaging those big questions of life, and ultimately to come to better know the author of the answers. And certainly the great questions of the humanities relate to the purpose and the content of the good life and the good society, what it is, what it means, and how it’s realized. And one of the greatest and most enduring challenges pertains to discerning and doing what is right in the midst of uncertainty, chaos, and opposition. Those in leadership, whether they’re leading a military or a political campaign, or a corporate restructuring or even a social movement, know that often the most difficult decisions come not when one is well rested, encouraged in possession of complete information, with ample leisure time to ponder all options. Rather, the hardest decision seemed to be made amidst exhaustion, under pressure, besieged by opposition with no margin and high stakes. It is then that wise leadership that can discern reality accurately, respond appropriately and rally others to the right is the most vital and the most rare. There are few leaders who face the magnitude of disaster, or the intensity of opposition that Abraham Lincoln did, much less lead with such resolution and remarkable grace. His second inaugural address, given just before the end of the Civil War in mere weeks before his own assassination, provides a remarkable view of his own struggle with the issue of slavery, his yearning for reconciliation in the midst of violence and struggle, and the extent to which his commitment to charity towards all was rooted in his own religious convictions. It shows the breadth of his own spiritual journey and his eagerness, in the words of the original sermon of the Mount, to bless and do good those who were his enemies. It’s a remarkable story of wise, gracious, and powerful leadership, and none tell the tale more insightfully, eloquently or enjoyably than Ron White. Doctor Ronald White Jr is a historian, a scholar, and the author of A Lincoln A biography, A New York Times, Washington Post, and LA times bestseller. The book was also honored as the best book of the year by The Watch, by the History Book Club and Barnes and Noble, and won the coveted Christopher Award in 2010, which salutes books that affirm the highest values of the human spirit. He’s also the author of Lincoln’s greatest speech, The Second Inaugural, which is itself honored as a New York Times Notable Book, a Washington Post and San Francisco Chronicle bestseller, as well as the author of The Eloquent President A Portrait of Lincoln through His Words, which was, of course, an LA times bestseller, a selection of the History Book Club, as well as a book of the Month Club book. When he is not busy writing bestselling biographies, he is lectured at the white House, the Library of Congress, the Lincoln Forum, among many other places, and including just Today and tomorrow, the Montgomery Bell Academy and Saint Paul’s Academy. He’s a graduate of UCLA and Princeton Theological Seminary, and has his PhD in religion and history from Princeton University. He also serves as a fellow at the Huntington Library and lives with his wife, Cynthia in California. Ron, welcome. It’s great to have you.

What a privilege to be here again. This is the third time I’ve spoken at Montgomery Bell Academy. We’ll do so again tomorrow morning. And my first time at Saint Paul’s Christian Academy this morning to the sixth graders. We had a great time. My first time to speak for the Trinity Forum, and I am honored to be part of this inaugural event for Nashville. I’d like to say that Abraham Lincoln is the man for all seasons. The Ken Burns documentary in the early 1990s brought him into focus. His 200th, the 200th anniversary of his birth in 2009, spread his word not simply in the United States. I was asked by the State Department to speak on Abraham Lincoln in Germany. I spoke in Italy and I spoke in Mexico, and I was fascinated by how people all around the world have this deep admiration for Abraham Lincoln. And now the Lincoln movie, whether you’ve seen it or not, we’re going to show a couple of clips in just a moment. The Lincoln movie is an attempt, I think, to offer two faces of Lincoln that are not always present. The first is the political Lincoln, the man of sagacity, the person who could work that Republican machine, who knew how to get things done. I kind of laughed about four weeks after the movie came out, one Republican congressperson said, well, he said, if President Obama thinks he’s going to pick us off one by one, just like Lincoln did, it shows what a president can do when he works with Congress. But the second part that I like very much is it humanizes Lincoln, the Lincoln of the Lincoln Memorial. But sometimes he is so larger than life that we miss his humanity. Did you notice if you’ve seen the movie, the Wonderful Humor of Lincoln, not some of the modern humor that often seems to me to put people down, but humor in which Lincoln laughs as much at himself as he does at others. I love the story. One of the key partnerships in the movie is with William Seward. You may know that William Seward, governor and senator from New York, was the leading candidate to become the Republican nominee for president in 1860. He led on the first and the second ballot, but Lincoln won the nomination. Lincoln offered him the position of Secretary of State and deeply wounded, Weward refused. Lincoln persuaded him to accept this position. One month after Lincoln was elected to office, Seward wrote him a letter mimicking actually the newspapers and said, we have no policy. Could I step forward and offer a policy that was something that secretaries of state did in the 19th century? Lincoln wrote him a letter the next day, April Fool’s Day, where he gave him the letter or spoke to him and said, if it’s all right with you, I’d like to be the president of the United States. One month later, Seward wrote a letter to his wife, who was still at their home in Auburn, New York, and he simply said to her, Lincoln is the best of all of us. Lincoln is the best of all of us. What a partnership. William Seward smoked 20 to 25 cigars a day. Lincoln didn’t smoke. Seward had a magnificent liquor cabinet at his home on Lafayette Square. Lincoln didn’t drink. Seward could swear a blue streak. Lincoln didn’t swear. One day they were riding in a buckboard together, and it was a bumpy road. And Seward, the as the they were going along. The driver was swearing a blue streak and suddenly Lincoln taps him on the shoulder and he says, my good man, are you an Episcopalian? And the driver, taken aback, kind of stutters a little bit and says, well, well, no, I’m a methodist. Oh, he said, I thought Episcopalian. You swear, just like Mr. Seward does. And he’s an Episcopal church warden. I want to start with a question for you. How many of you have been to the Lincoln Memorial? Almost everyone. It was exciting that the sixth graders at Saint Paul’s are going to Washington on their school field trip the second week of May. To your mind, the first time you were there, or maybe when you were there with children or grandchildren? I always loved to go to the Lincoln Memorial when I’m in Washington. You recall as you arrive and look up those steps, there is this 28 foot high Daniel Chester French statue of Lincoln. You get to the top of the steps. I was telling the children this this morning, and in a noisy city, suddenly everybody is quiet and people are looking at the left there. One panel is the Gettysburg Address, and on the right, carved in three panels in Indiana limestone is the second inaugural address. What some of you, this is going to be very interactive. Would some of you be willing to just say in a word, What was the feeling or experience that you had when you were at the Lincoln Memorial? Anyone in the good acoustics of this room? What’s the feeling that came to you or your experience. Reverence? Well, those are two pretty good words. I like to say, however, that awe is not the same thing as understanding. We can go to a concert. We can feel the awe of music. When I was in college, I had the privilege of singing in the a cappella choir at UCLA, directed by Roger Wagner, the founder of the Roger Wagner Chorale. And when we sang the Saint John’s Passion, or the Missa Solemnis, it was awe inspiring. But I realized I didn’t really understand the music. And so in my senior year, I took a non-music major course, one course on Bach and one on Beethoven. I’ve written my Lincoln biography not for the so-called Lincoln file. But for the person who isn’t so familiar, I am more thrilled when a 12, 13, 14 year old comes up to me and says, I have read your book on Lincoln, and let me tell you what I learned from it. That to me is what’s really exciting. The Next Generation, the Lincoln movie concludes with the second inaugural, and there’s a debate about whether that’s the right way that it should have concluded. Many people think it should have concluded earlier, but the purpose of this evening is to say the movie concludes with only part of the second inaugural. Only a fraction of the second inaugural. What we’re going to do this evening is to try to understand the whole message of the second inaugural, and especially faith, message and journey that is embodied in those words. But to set this in the right context, I’m going to ask us now to look at two small clips, consecutive clips from the beginning of the movie that begin to put into perspective the Lincoln that I would like to present this evening.

I thought I lost you, Lily. Me too. Daddy. But we can’t. It’s three years now. It’s gone.

The part assigned to me is to raise the flag, which, if there be no fault in the machinery I will do and when up. It’ll be for the people to keep it up. That’s my speech.

Of the day. 300,000 for the Mississippi. Pine trees and rounded wings. And soar to a thousand workshops of lightning.

Even if every republican in the House votes yes for.

I’ve chosen these two scenes because they say a great deal about Lincoln. But you don’t fully understand them. Especially the first one. I’ve seen the movie four times. And what is going on here? We don’t know the full story. Almost the central event in Lincoln’s presidency is the death of his son, Willie. We never want to say one son or daughter is more than the other, but this was the boy most like the father. Mary never, ever recovered from the death of this son. She actually wrote a letter to Willie’s best friends, and asked the mother never to send her son and daughter to the white House again, because they reminded her of Willie and she could not stand it. She could not attend Willie’s funeral. She was so filled with grief. So the boy that is left is Tad, and he is bereft of his older brother. And Lincoln bends down. And what’s remarkable is, what is he looking at? Tad is looking at pictures of African American children. And what Spielberg and Kushner are saying to us is that for 75 years of Lincoln films, the Great Emancipator disappeared, but no more. The Great Emancipator has come back into this movie. First, he disappeared from white writers that wanted to denigrate that. Then he disappeared from black writers who said Lincoln doesn’t deserve to be called the Great Emancipator. They emancipated themselves. And so Abraham Lincoln bends down in a wonderfully tender scene and kisses this son, and the son gets on his shoulders and literally for 24 hours a day for the rest of the time in the white House, Lincoln will begin to sleep with the son. The son will be in the cabinet meetings. He will be everywhere. And it shows the remarkable humanity of Abraham Lincoln. Then I love the second scene, which has a kind of a jovial figure to it. He’s actually true. He took his speeches out of his hat. But notice what he says. It’s up to the people to keep it up. Lincoln had this remarkable trust in the people. This is what was going to do it. And so at the end of his presidency and the end of the film, he delivers the second inaugural address. And for those who say the film should have ended earlier, what the film writer is saying is Lincoln didn’t die. We saw his death on film. We watched his assassination. But I like to say to students, Lincoln is one of those few figures who is still alive, and he’s alive, in his words. We all have studied in the college and the university of our choice words of remarkable people in literature and politics and economics. But there’s very few of them, I would suggest, whose words we still speak today. And I believe that 50 and 100 years from now, people will still be speaking Lincoln’s words. So let’s look at those words this evening. I’ve given you the handout of the second inaugural address. It’s only 701 words, the second shortest inaugural ever offered. George Washington offered the briefest. He didn’t want to run for a second term and there was no tradition. And so I like to say that George Washington stood up and said, thank you very much in 135 words, and sat down, but people were taken by surprise. We know how long inaugural addresses are 701 words, but Lincoln mentions God 14 times, will quote the Bible four times, and will invoke the prayer three times. And this took his audience by surprise. The next day, a newspaper writer said this was Lincoln’s sermon on the Mount. I wanted that to be the title of my book, but the New York publisher said, oh no, we couldn’t use that title. Another newspaper writer said he’s crossed the line between church and state. Oh my goodness. And a third said, this is the tale of an old sermon. We need to know who was there that day. Some of you have been to inauguration. It’s the candidate of your choice. It’s a very exciting event and so I expected that everyone there would be excited. But when I read their letters and diaries, I found quite a different emotion. Many of the people there were filled with a deep anger. Anger. Why anger? They were angry at the South. They wanted Lincoln to give voice to that anger. In World War One, we stopped the teaching of German in every public school in this nation. In World War Two, we banished the Japanese from the West Coast. That’s what we do in times of war. And Lincoln, thinking about all of this, brooding about it deeply decides to offer a very different kind of address than the people that day expected. He begins at this second, appearing to take the oath of the presidential office. There is less occasion for an extended address than there was at the first. This is not exactly fourscore and seven years ago. We’re not sure where he’s going. I know the Trinity Forum focuses on leadership, and I would suggest that in the first paragraph, Lincoln breaks every law of modern leadership studies the modern politician. Pardon me. With all due respect, I often will say, this is what I will do. This is what I promise. This is what we can do. Lincoln takes just exactly the opposite approach. Listen. Line two. There is less occasion for an extended address than there was at the first. Line seven. Little that is new could be presented. Second line from the end of the first paragraph. No prediction in regard to it is ventured. What an unusual way to begin an inaugural address. When we get to the second paragraph, I suggest we begin to get a sense of where Lincoln is going. Lincoln is asking himself a question that no one is asking. Sadly, not the preachers, not the politicians, and not the professors. He’s asking this fundamental question how can the South be brought back into the Union? And he understands that if the South is meant to bear the blame and the shame alone for this civil war, they will never be able to be brought back into the Union. So he begins with what I call inclusive language. He wants to include everyone in this address. Listen. On the occasion corresponding to this, four years ago, all thoughts were anxiously directed to an impending civil war. All dreaded it. All sought to avert it. Here he is imputing the best possible motives to the people of the South. Contrary to those in his audience who are imputing the worst possible motives to the people of the South at the end of the second paragraph. Both parties deprecated war. His wonderful use of inclusive language. What a marvelous lesson for those who are involved in politics. We may disagree, but to impute the best possible motive to the person or party on the other side. Now, the first time I ever gave this address was at the United States Air Force Academy. The first time I talked about the second inaugural. And wouldn’t you know, among the faculty that day was a Princeton PhD in English. And he challenged me when we got to the end of the second paragraph, he said, doctor, why don’t you see that it says both parties deprecated war, but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive? Isn’t Doctor White actually imputing blame to the south? Yes. But when we listen to politicians, professors, preachers, we need to listen to what they do not say as well as what they do say. For just imagine for a moment if Lincoln had said this. Both parties deprecated war. But those traitors, that enemy, those Confederates, those tyrants. Why, he knew that the audience would have swelled with emotion. And I believe, very self-consciously, he decided to use the generic language, but one of them to lower the decibels, to not call out the emotion, which it would have been so easy to do. This morning, as I looked at these children and marveled at the wonderful education they are receiving, I reminded them that Abraham Lincoln was the beneficiary of but one year of formal education. Most girls did not receive education. Boys who worked in the fields only received education in January and February, when they could not be in the fields, and altogether Lincoln had but one year of education. The education, however, was different than ours. Maybe it’s not different than ours here at these two wonderful schools, because the grammar book that he first started using when he was 21 years old was divided in two, and the last half of it was what was called declamation, declamation, passages from the Bible, passages from Shakespeare. So he was taught at an early age to be what people called in those days a public reader. And he grasped the beauty of the written language. I so fear that we are dumbing down the English language in our time, that young people are not learning the beauty of language. When I taught a year ago at UCLA and students in my seminar turned in a paper, I respectfully said to them, thank you very much. This is a first draft. First drafts are not acceptable at a school like UCLA. And I said there is no such thing as good writing. There’s only good rewriting and rewriting and rewriting. And Lincoln understood this. So in the second paragraph we see some of the rhetorical abilities. First of all, and here’s an extra credit question. What is alliteration? Yes.

You say a phrase and all the words begin with the same letter.

My goodness sakes, alive. Wonderful. Thank you very much. This young gentleman understands alliteration perfectly. Terrific. Let’s listen. On the occasion corresponding to this, four years ago, all thoughts were anxiously directed to an impending civil war. All dreaded it. All sought to avert it. While the inaugural address was being delivered from this place, devoted altogether to saving the Union without war. Insurgent agents were in the city seeking to destroy it without war, seeking to dissolve the Union and divide effects by negotiation. Both parties deprecated war. Now a little bit older than you answer that question for me. Recently in Phoenix, Arizona, and as I was beginning to unpack this paragraph, her friend sitting next to her leapt up and said, do you mean to tell me that Abraham Lincoln decided to use the consonant D eight times in the second paragraph? No. But he had a sense for what I call the musicality of language. For what does alliteration do? Alliteration is an invisible tissue connecting words together. Preachers like to use it because it connects ideas together. We may not even be conscious of what’s happening to us, the listener, but it’s a wonderful way of telling the story. And almost like in music, there’s a crescendo in this second paragraph. It’s building to a remarkable complex. Lincoln had another, uh, in his arsenal of rhetorical strategy. It was the use of the same word over and over and over again. If you only have 272 words at Gettysburg and 701 words in the second inaugural, why not use the same word? So look carefully at the second paragraph and see if you can find the noun that is in every single sentence. This is the reason that people are there that day. This is the conversation. Everybody’s mind. The word “war”. And the word “war”, I suggest, is the direct object, both grammatically and historically, of the actions of the soldiers, the generals, and of Lincoln as commander in chief. Until we get to the last sentence, until we get to the last sentence and suddenly the war is no longer the direct object. It has become the subject. When I spoke that day in Colorado Springs, my guide was a marine Corps major who told me that in one engagement in Vietnam, he was wounded 38 times. He then went on to earn a PhD in philosophy to earn his Master of Divinity degree and become a chaplain and helped institute at the Air Force Academy, their institute on ethics. And he said to me something I didn’t fully understand at the time, but he said, Ron, when the next war comes and it will come, he said, we will be told by our government and by our military that we are in control of the war. He said, do not believe it. We are not in control of the war. We are never in control of any war. And then he said to me, Didn’t Lincoln understand that? And the North was going to win this war very quickly because they had more men in arms, they had a much greater industrial base. But the war went on and on and on and on. And Lincoln had come to the realization that he was not in control of the war. The generals were not in control of the war. And so he offered this nominal final sentence of the second paragraph. And the war. Now I wondered, how did he say this sentence? We actually have photographs of Lincoln delivering the second inaugural. I thought, well, maybe he would say it like Edward Everett, who spoke for two hours and seven minutes at Gettysburg before Lincoln. How would you like to follow that? Edward Everett, who’d been president of Harvard, who was the greatest orator of the land, who would have said it something like. And the war came. But I don’t think Lincoln said it that way at all. Would several of you just suggest how you think Lincoln might have offered this final line of the second paragraph? What would be his tone or his attitude. With resignation. How can we cheer when we thought it was 620,000 dead in the last nine months? A new demographer taking the United States Census into being has discovered it wasn’t 620,000 dead. It was 750,000 dead. And now all historians affect that. We have anguished as we should, over the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Do you know that tiny nation, if we were to compute it, or today, it would have not nearly 5000. Can you imagine what that meant in the small towns of this nation? I told the children that I was in Krakow, Poland, some years ago, in the darkest days of communism, and was having a luncheon meeting at a church there. And as I sat around the table talking with the people who were there, I noticed that all of the people were women. And I said to the women, it was the middle of the day. I said, well, where are the men? And the woman next to me said, there are no men. There are no men. All the men of our generation are gone. They’re all gone. That’s what it was like to live in Poland. Not quite the same, but very much the same. To live in the Civil War. All the men are gone. And Lincoln understood this. In the third paragraph, Lincoln offers the strongest summary of what the Civil War was all about. Charles Francis Adams Jr, the great grandson of John Adams, the grandson of John Quincy Adams, whose father was minister to England from the United States, was in the crowd that day. 29 year old soldier, he wrote to his father and he said, isn’t the rail splitter a wonder? First at Gettysburg and now in the second inaugural? This will become the historical keynote of this war. And so it is. And so Lincoln says. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All new. Notice the inclusive language that this interest was somehow the cause of the war. The cause of the war. Now, if you turn your page and come down to the third line from the top, I suggest that Lincoln suddenly shifts the tone and the emphasis of what he is saying when he says both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes his aid against the other. A surprising place of my research for Abraham Lincoln’s second inaugural address was the American Bible Society in New York. It’s the only voluntary society founded in the 19th century that still exists in the 21st century. And if you go there, Some of you get to New York, put that on your list of places to visit, because in the archives there you will find these remarkable collection of Bibles, Union and Confederate, often with blood on them, almost always with the soldier’s life verse penned at the beginning of the Bible. And what Lincoln is saying to northern audiences is the Confederate soldiers read the Bible every bit as much as the Union soldiers do. The people of the South read the Bible every bit as much as the people of the North do. But then Lincoln uses the semi-colon. I kind of have a fun conversation with Brad, because the first time I spoke at at MBA, he told me, understandably, he said, we cannot hand out 700 pages to avoid 700 boys who know what they’ll do with them. He said it’ll be on the internet. So I turn around and look at the internet. He didn’t know, but I understood right then. Some modern person on the internet had completely changed the punctuation of the second Inaugural address, there was no longer a sentence at the end of the second paragraph. All the semicolons were gone. All the dashes were gone. We thought we’d modernize Lincoln. Lincoln loved the semicolon, and so should we. So that Lincoln says both sides both read the same Bible and pray to the same God. That’s an affirmation. But then he changes his voice and each invokes his aid against the other. How dare each side invoke his aid against the other? Do we worship a tribal god? I’m tired of this talk. Jefferson Davis gets the talk. I get the talk that God is on our side. And each invokes his aid against the other. It may seem strange that any man should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces. This is Genesis 3:29. This grows out of a conversation that Lincoln had with two women from the South whose husbands were Confederate officers confined to a Union prison. He had it three months to the day before he offered this address, and the women came to him and said, we want you to release our husbands because they are religious men. And Lincoln invited them back a second day. They were surprised, and then he invited them back a third day to continue the conversation. And finally he said to them, I find it very difficult when you tell me your husbands are religious men. And then, as he could do so easily, he quoted Genesis from memory and told them he didn’t think this was the kind of religion that got people to heaven. So he kept this in his mind. But the moment he says that, he offers another semicolon, but not that we be not judged. Matthew seven verse five. This is Jesus sermon on the Mount. For Jesus offers an ethic not of judgment, but of mercy, of forgiveness and grace. We may ask this question during the question and answers. What is Lincoln’s understanding of Jesus? Here he invokes Jesus words, and this is why the newspaper reporter picked it up correctly. This is Lincoln’s sermon on the Mount, and now we’re going to see grace and reconciliation intersect these words. The prayers of both but neither has been answered fully. And then what I call Lincoln’s fundamental indicative of this address. The Almighty has his own purposes. Lincoln’s favorite word for God was the Almighty. Lincoln once was attending the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church, and Noah Brooks, the reporter for the Sacramento Daily Union who had known Lincoln, arrived in town. And the minister said, let us pray. And Brooks did what you shouldn’t do. He kept his eyes open, and he looked down on all those people on the first floor. And he noticed one gentleman stand. When the minister called for prayer, and afterwards he asked Mr. Lincoln. Why did you stand? He said, that’s my mark of respect. God is the Almighty, and I stand in respect before the Almighty. Wow. Now Lincoln offers yet another change in his inaugural address. I like to say, and, Senator Frist, you can help me if this is true or not, that sometimes, and I want to say this lovingly inaugurals are kind of efforts or self-congratulation. Oh, thank you so much for electing me to a second term. I know you know what a wonderful job I did the first time. Thomas Jefferson says that in his second inaugural, or they are kind of efforts of self-congratulation to our nation. We are such a great nation. Lincoln does something. It’s that’s not done in any inaugural address. He dares dares to tell this great nation. He thought it was a great nation, that there is something fundamentally wrong at the heart of the community. Woe unto the world because of offenses. For it must needs be that offenses come. But woe to that man by whom the offense cometh. I suggest that here Lincoln sounds like a Puritan preacher preaching a jeremiad. The second and third generation of preachers in New England said to their constituents, you have forgotten the faith of your parents and grandparents. You have become immoral. You become this, you become that. Well, what is the offense? Lincoln says, if we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses. But remember what I said, if Lincoln would have said, if we shall suppose that slavery is one of those offenses, why, this northern audience might have erupted in applause. That’s the problem there. The problem? No. Lincoln, I think, very self-consciously uses inclusive language. We are all part of this problem. American slavery, which in the providence of God must needs come, but which, having continued through his appointed time, he now wills to remove, and that he gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came. Shall we discern any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to him? I’ve been challenged on this sentence and said, well, Lincoln is not saying I believe in a living God. Well, this is the way Lincoln wrote. This is the way he spoke. In 1864, a group of soldiers came to visit him in the white House, and he said to them, you know, this is the most wonderful country in which we live. Any of your children could one day become president of the United States. Just like my father’s child has. Just like my father’s child has. When he was asked to write a campaign biography in 1860, he wrote it in the third person. Lincoln disappeared in his two greatest addresses. No personal pronoun in the Gettysburg Address. Only two in the Second inaugural. How different from the way we speak. Or the pronoun I is so prominent in our discourse. Finally, do we hope fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away? Yet if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondman’s 250 years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said 3000 years ago. So still, it must be said, the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether. Psalm 19:9 I said to someone over the refreshment time that I submitted and was published by the New York Times on January 20th, a op ed on inaugural addresses and on Lincoln’s marvelous second inaugural. I learned the New York Times as a fact checker. They said, you can’t believe all the people that want to nitpick our pieces in the New York Times. So we’re talking back and forth, and he says, you say there’s four verses of the scripture in here. I can only find three. I said, how about trying? The judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether. Look it up. Psalm 19:9. Now, up to this point in time only, there were only four occasions of applause, according to the reporter for the New York Herald. Therefore, the Times of London. Sometimes when you stand outside your own culture, you see things more clearly. It was a dark, windy day. 25,000 people were there. And the reporter, early on, as he began to craft his story, noticed that there was a group of people there who were kind of all sort of staying in the back, but they were dressed in more brightly colored clothing than anybody else. And when we get to this moment in the address where he talks about 250 years of unrequited toil, he began to hear something and he leaned forward. He tried to hear what was being said, and then he heard that it was being passed forward. Oh, yes, he could hear it. Bless the Lord. Bless the Lord. Bless the Lord. Bless the Lord. The African Americans in the crowd who had never been to an inauguration in their life. They understood what Lincoln was saying. Bless the Lord, bless the Lord. Sermons then and now are not too different. I like to suggest that a sermon basically consists of two parts, I should say. Frederick Douglass, the greatest African American of the day, was in the crowd that day. He wrote in his diary that evening, this was not a state paper. This was a sermon. And if it was a sermon, the first three paragraphs are what I call the indicative, where the preacher, the priest, the rabbi announces to the congregation, this is what God has done in leading the people through the Red sea in the life, teaching, death, and resurrection of Jesus. This is what God has done. But most ministers, priests, rabbis that I know at the end of the sermon will finally get to the place where they’ll say something like. And now, dear friends, in the coming week, I ask you to. This is the imperative. This is the ethical imperative. How are we to respond to the indicative? I’ve asked myself. I’ve. I spent hours thinking about this. What do you think Lincoln was thinking as he penned this address? Two men came to his office the week before on a Sunday evening. He was carrying it in his hand and they said, what is this? He said, this is my second inaugural address. He said, it’s only 600 words. So obviously he edited it. Lincoln was asking himself the question, is it possible for a nation so deeply divided to reach out in forgiveness and reconciliation? It’s a question that can be asked today. Is it possible to reach out in forgiveness and reconciliation? And so I think we should put an unvoiced. Therefore, at the beginning of the last paragraph, it’s like the letters of Paul where Paul will take the first three chapters and sort of declare what God has done in Christ, and then he will say, therefore I ask you to. And Lincoln is asking something therefore with malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right. But I think to fully understand what Lincoln is saying, we need to say those words aloud. Lincoln always read out loud. He read out loud. Mary read out loud. That’s what people did. Because I think somehow, although I want to be very careful in positioning Lincoln as a man of the 19th century, I think somehow Lincoln still speaks what the movie suggests. His words are still alive. He can still offer us a way of leadership, a humility that we desperately need, and inclusive spirit, a way of reaching beyond ourselves to value the other. So may I suggest, in conclusion, before we have your comments and questions that we say together, Lincoln’s conclusion together with malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right. As God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow and his orphan to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and a lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations. Thank you.

…speech on Lincoln. They were all mesmerized by Doctor White, so I appreciate that very much as a former prep school English teacher, I must confess that right before Doctor White arrived on campus, I read the second inaugural aloud, and we talked about and lamented a little bit that we don’t use the spoken word in such ways anymore. But, uh, beautiful writer Abraham Lincoln is, um, and is my, uh, my pleasure to ask the first question for this evening. And my question, Doctor White, is this knowing Lincoln as you do, uh, what do you what counsel do you think that Abraham Lincoln would give an aspiring president of the United States today in the context of our political landscape?

That’s a good question. I’d like to say to audiences, uh, when I first started talking about Lincoln, Bush was in office, and people would say to me, what would Abraham Lincoln tell President Bush about the war in Iraq? And I would say, I have no idea. I don’t think Lincoln can answer for us climate change or anything else, but he can offer to us a spirit. And part of the I think, intent of the movie is to ask modern presidents, although we do have three different branches of government, to be more directly involved Congress was to move forward. And I think Lincoln’s spirit remember now that he put into his cabinet his chief rivals for the Republican nomination, all of whom thought they were more experienced than he was. And he also put into his cabinet prominent Democrats. It seems almost impossible to do that today. I mean, we have LaHood in President Obama’s cabinet, but he’s retired from his congressional seat in Illinois. And so I think this idea of respecting the views of the other side is so fundamental that it is his magnanimous spirit. If I could use one word to describe him, it would be magnanimity. I think that’s the spirit that any modern president needs. Yes.

It’s becomes more of a trite statement than if Lincoln had only lived. The South would not have been oppressed. That’s mainly, I think, by the second generation, after the war. Uh. Do you. What do you think, Lincoln, how would he have approached either reconstruction or the healing of the South?

If I may repeat what you said the comment is, and you suggest that it’s often been made. If Lincoln had lived that what happened between the North and South would have been different. And I think it would. Johnson was really sort of a disaster. I don’t think Lincoln actually picked Andrew Johnson. I think that was picked by the convention, which was the precedent in those days. The vice president. Anyway, Lincoln combined this remarkable spirit of forgiveness and a spirit of strength. The irony of all of this is that Lincoln’s greatest foes were in his own party. They were the Radical Republicans. They were the ones who wanted to destroy the South, to wreak revenge on the South. And a friend of mine who’s writing a wonderful Lincoln book that’ll be published by Norton, sort of on the aftermath of all this, really comes up with the idea that many of these Republican leaders almost were glad that Lincoln was no longer on the scene because he was too soft. He was too reconciling. He was too forgiving. Now, the South didn’t fully understand this. There were only 4 or 5 newspapers still publishing at the end of the Civil War, and the Petersburg Gazette published the editor. About ten days later, and he was clearly puzzled. He said, why, this man seems to be a student of the scriptures. He seems to be a person who is for peace. Well, I guess I can only say with him, let us judge not that we be not judged. So, sadly, and this is so often true, isn’t it, that we see not the best side, but we see people through a caricature. And so the North saw the South as a caricature, and the South saw Lincoln through a caricature.

I recently read that Lincoln had had, in his brief term as a congressman, a connection with John Quincy Adams and that there was some sense of mentoring there that occurred. And so you think, despite the passage of time of Lincoln as kind of one of the founding fathers of the nation, in a way, maybe the last one and kind of imbibe their spirit. And I wonder if you had thought about that connection.

The question is, what was the connection in Lincoln’s single term in Congress with John Quincy Adams? John Quincy Adams is that rare individual who, after serving one term as president, is elected to Congress and serves until he dies in Lincoln’s first term. I’m not sure I would say he’s a mentor. I don’t know that they had such a close relationship, but he looked upon him with great admiration. And so there’s that aspect, certainly. He was the kind of father figure of the of the party at that time. And so Lincoln had great respect for him. But he died shortly after Lincoln came into Congress.

Thank you for that. Who were Lincoln’s brothers? Who does he walk with through this time? That’s got to be a lot of weight with this family. What’s going on in his life?

Wonderful question. The question is, who were Lincoln’s brothers? Who did he walk with? David Donald, great Lincoln historian and biographer, wrote a book some years ago on Lincoln’s friends. And in one sense he said Lincoln didn’t have any friends that in a certain sense he was lonely, that he was locked into this difficult but loving marriage. I am not a person that wants to bash Mary Lincoln. Someone who has lost one son and then a second son. I’m not into that. But then, uh, he is struggling with all of these issues. Seward becomes his best friend, and they try to force Seward out of the cabinet in December of 1862. John of Kentucky was his best friend, but they ended up having different views on the secession slavery. So although I’m presenting Lincoln as quite a remarkable figure, it is not that he had this close group of friends. Even in the movie i think you sense a certain loneliness that’s there. And of course, then Mary, as she is just consumed with grief, they have their own struggles. She sort of asks him, why aren’t you grieving? He is grieving. He says, I am the president of the United States. I have this office. I cannot allow my grief to really just destroy me as it’s destroying you. So there’s a moment here.

Have you ever looked at the life of Andrew Jackson compared to Abraham Lincoln? They seem to have such high principles in trying to bring people together.

Have I ever looked at the life of Andrew Jackson in relation to Lincoln? This is an interesting question because Lincoln rose as a Whig and the Whigs jackson didn’t get along together, and so he was raised as a young man to despise who they call King Andrew, who was going to be this despot even though he was supposedly the people’s president. But who did he have a photograph of or a painting of in his office? Andrew Jackson, because he learned what many politicians learn that when you sit in the office, you suddenly see things differently. And he had a whole new respect for Jackson. Once he sat where Jackson sat.

Do you ever talk about Lincoln or this topic in other cultures that don’t share this narrative that he was drawn upon and how do they perceive this?

I’m glad you asked that question. Have I, as I’ve spoken about in other cultures who don’t have this narrative to draw upon? How do they respond? Well, I spoke at the United States consulate in Hamburg, and we spoke to 12th and 13th grade teachers. And I asked them, why are you so fascinated with Lincoln? And they said, well, let’s put it this way. We know American history, and they do. And we know George Washington, and we know Thomas Jefferson, but we think of them as rather well-born, kind of aristocratic figures, like many of the people in our history. But we think of Lincoln as what America is all about. I love Lincoln’s phrase, the right to rise, the right to rise. And so we think of Lincoln as the best of what it means to be an American. I was speaking in Berlin later in that trip, and I was speaking at the Free University, which has the greatest American studies center in Europe. And we went out to dinner afterwards to an Italian restaurant. And I’m sitting next to this graduate student. And he said to me, his first language is German. He said, I love Abraham Lincoln. He said, May I recite to you from memory Abraham Lincoln’s farewell address at Springfield when he’s leaving for the presidency. And I’m listening to a German student speak in his second language from memory. Abraham Lincoln’s farewell address at Springfield. When you go to Mexico, uh, there’s a tremendous love of Lincoln in Mexico. I wasn’t able to go to Monterrey because of all the violence there. But there’s a mural to the three great liberators of the Americas. And Lincoln is one of the three great liberators. And so wherever you go, someone just handed me a book. I was speaking in Phoenix, and someone gave me a book on Lincoln in Korea. And I’m reading this book. I learned that Abraham Lincoln is hero in South Korea. He represents the values of democracy. So wherever you go, you will find this fascination with Lincoln.

In the movie, we got to hear several of President Lincoln’s stories, and he always enjoyed them. Right. Like everybody else didn’t know what would you talk a little bit about his storytelling. And then if you have a story that wasn’t in the movie.

A great comment is that the movie had some of Lincoln’s stories. He enjoyed the stories. You recall that scene in the movie where they’re in the telegraph office, and they’re waiting for the report of the battle to come in, and he starts to tell a story, and Edwin Stanton says, no, no, you’re not going to tell one more of those stories, are you? And then what you don’t see, you’ve got to see it the second or third or fourth time when the news of the battle comes in, Lincoln and Stanton are holding hands. What you don’t know is that Lincoln in 1859 was a great law case called the Reaper case between two different men who had invented the reaper. Great advancement in agriculture. And the case was to be tried in Chicago. And so they said, we need to have an Illinois lawyer do some of the spadework for us. We’ve heard of this fellow Lincoln in Springfield. They hired him to do all the due diligence. Then the case shifted to Cincinnati. Lincoln arrives for the case, and Edwin Stanton is the leading lawyer. And he said, we’re not going to engage that buffoon. We’re not going to have that gorilla. He’s not going to sit at the table with us in the front. He’s not coming to the social event. He absolutely humiliated Lincoln. And when the first Secretary of War doesn’t cut it, who does Lincoln turn to? To be the Secretary of war, Edwin Stanton, the man who had humiliated him. And you recall then, that scene towards the end of the movie, when Lincoln is dying there in the Petersen house and when he expires, Stanton is the one who says, and now he belongs to the ages. So the ability of Lincoln to take even those people who were so critical of him and not to hold that against them, but to recognize that Stanton had all the abilities to become, as he did, a remarkable secretary of war that says so much about his leadership, his intuition. We have time for one more, before Cherie Harder closes our evening.

Abraham Lincoln had a lead. What was his role with Robert E Lee?

Ronald White Jr.: What was Lincoln’s relationship or role with Robert E Lee? Well, after the war, Lincoln did not live long, so. Well, Lincoln, when when the war began, he tendered through his friend the command of all the Union forces to Robert E Lee. He recognized Robert E Lee. What I found remarkable was that when Stonewall Jackson was killed, this terrible killing by his own men, inadvertently, Lincoln wrote a letter to the editor of the Washington newspaper and praised Stonewall Jackson as a Christian gentleman and as a great soldier. Wow. Can you imagine something like that happening? So I think Lincoln had, as so many did in the North, great, great respect for Robert E Lee. And of course, the person that I’m working with now, I’m doing a biography of Ulysses S Grant. When there was the someone were going, let’s let’s prosecute Lee. Let’s put him in jail. Grant literally said, over my dead body you will do that. We will not prosecute Robert E Lee. So there was, I think, a remarkable, deserved respect for him. You’ve been very generous in listening and commenting and questioning. Thank you.

Thank you Ron. That was absolutely fabulous. There are so many people to thank for tonight’s gathering. I just want to thank our host committee again, Governor and Mrs. Haslam, Bill Frist, uh, Joe Cook, Mr. and Mrs. John Rochford, and of course, Byron Smith. We so appreciate that. I also just want to thank Brad Gioia and the Montgomery Bell Academy and Ken Cheeseman and Saint Paul’s. It’s been a delight and a pleasure to work with you both. On your chairs you should find a couple of handouts. We are hoping that this is not the last time that we will be in Nashville, but that this will be a launch event for an ongoing presence here. And we wanted to invite all of you to be part of that. On your chair, you should see a small response card that asks whether you’d like to be part of a host committee in the future, and if that’s something that you’d be interested in, we’d love to talk with you. And you can simply just leave these cards either on your chair or hand them to my teammate Lucy Lafitte in the back. And Lucy, you can just wave. It also asks whether you’d like to be part of a reading and discussion group. And one of the things that we do, in addition to having programs such as this that really provide a platform for the best of Christian thought leadership, is to encourage and catalyze different reading and discussion groups across the country that meet together on a quarterly basis to discuss our readings, which generally feature an excerpt from a work of classic literature, along with discussion questions to help one engage its purpose, its import, and its impact. And if that’s something that you would be interested in, again, just let us know and we’ll follow up with you. Finally, you should have on your chair a brochure that invites you to join the Trinity Forum Society. And the Trinity Forum society is really just a group of members that help make events like this possible. There are folks who receive our readings on a quarterly basis, receive different podcasts, different intellectual and thought resources to help them in their thinking, as well as invitations to events like these and others worldwide, and to provide an extra additional incentive for you to join the Trinity Forum society. If you join this evening, we will give you a copy of Ron White’s book, Abe Lincoln, which I’m betting we can prevail upon him to to autograph at the end of the evening as well. Finally, I’d just like to thank a few additional people to acknowledge our chairman of the board, Price Harding, who’s here tonight and has flown in from Atlanta, as well as my colleague Lucy Lafitte, who’s done a great deal of work in making this happen, and Nancy Crowell from Saint Paul’s and Jennifer Howell from MBA as well, who’s done just a huge amount of work to make this such a fantastic evening. Finally, thanks to each of you for coming. We’re delighted to have you here. And good night.